On the Correspondence Ludwig Wittgenstein – Ben Richards

“I’m thinking of you constantly with love”

24 November 2021

by Dr. Alfred Schmidt, Austrian National Library. German original here.

The extensive correspondence between Ludwig Wittgenstein and Ben Richards, of which the Austrian National Library was recently able to acquire another significant part, provides touching insights into the last years of the important philosopher’s life.

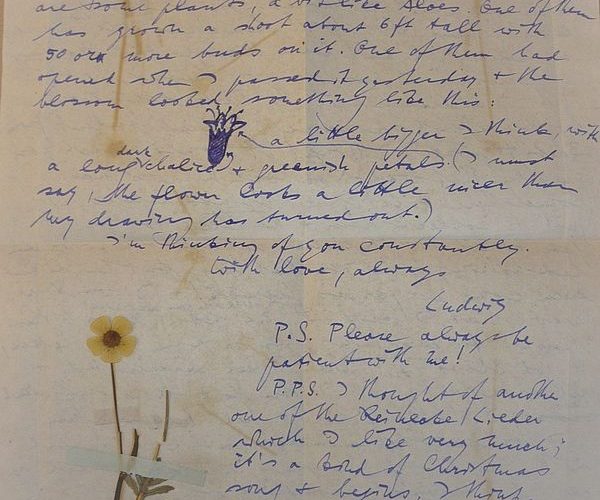

Fig.1: Ludwig Wittgenstein and Ben Richards in Dublin, 1948

The last five years of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s life were marked by a deep emotional relationship with the London medical student Ben Richards (1924-1995), who was 35 years his junior. The love for Richards changed Wittgenstein’s entire perspective on life and became the focus of the last years of his life. Their close bond lasted from autumn 1945 until Wittgenstein’s death in April 1951.

The first of a long series of letters between Wittgenstein and Richards date from June 1946. As early as 1995, shortly after Ben Richards’ death, the Austrian National Library was able to acquire from his widow Tara 150 letters from Wittgenstein to her husband. In accordance with Ben Richard’s testamentary wishes, they remained closed to the public until 2020. In the course of preparing an edition of this collection of letters, Miranda Richards, Ben Richards’ daughter, informed me that more letters from Wittgenstein and her father are in her possession: namely, more than 100 letters from Ludwig Wittgenstein to Richards as well as more than 80 responses from the latter to Wittgenstein, plus numerous greeting cards, telegrams as well as photographs (Ben Richards’ letters to Wittgenstein were returned to him after Wittgenstein’s death in 1951). In 2021, the Austrian National Library was able to acquire also this previously completely unknown part of the Wittgenstein – Richards correspondence. The new letters fit exactly into the gaps of the already existing collection of letters, which now covers a period from June 1946 to April 1951. Richard’s letters of reply supplement the hitherto one-sided correspondence and allow an even more detailed picture of this last and closest relationship in Wittgenstein’s late years.

This is the largest discovery of unknown original sources on Ludwig Wittgenstein in the last 25 years and the quantitatively most extensive correspondence on Wittgenstein ever. The important Wittgenstein resources in the Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books of the Austrian National Library have thus been expanded by a significant aspect. A publication of the entire correspondence between Wittgenstein and Richards is in preparation.

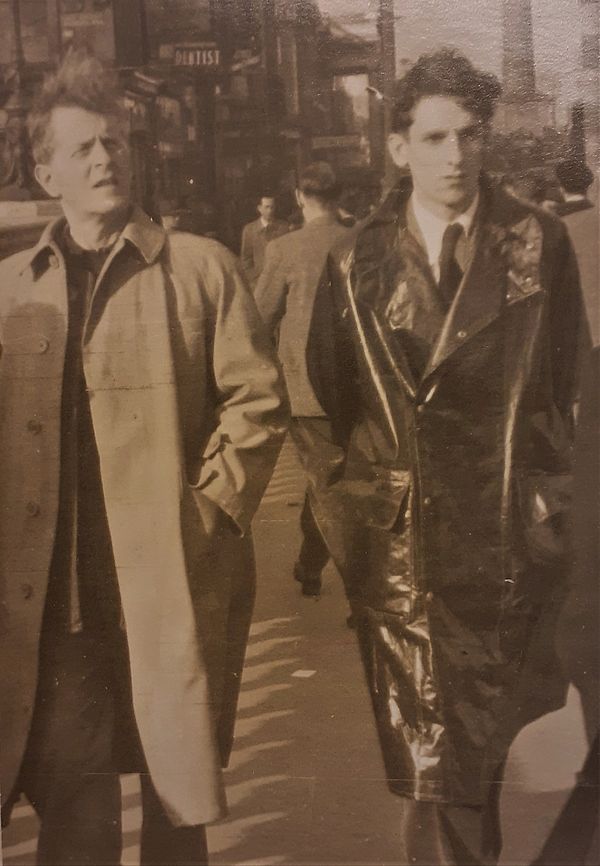

Fig.2: Letter from Ben Richards to Ludwig Wittgenstein, Christmas 1946

Ben (Robert Benedict Oliver) Richards was born into a London family of physicians. His mother, Noel Olivier, brought up in a left-liberal home, was, together with her three older sisters, a colourful figure (1). Virginia Woolf described the circle of friends around the Olivier sisters and the English poet Rupert Brooke (1887-1915) as “Neo-Pagans” because of their down-to-earth, liberal lifestyle. Brooke, who became a national idol in Britain after his early death in the First World War, fell passionately in love with Noel (2), when she was only 15 years old. Along with her three sisters, she was close to the Bloomsbury Circle and the Apostles. The father of the four Olivier sisters, Sydney Olivier, was for many years British Governor of Jamaica, and also one of the leading figures in the socialist Fabian Society and a close friend of figures such as H.G. Wells and G.B. Shaw.

Wittgenstein met Richards at the end of 1945 as an auditor at his lectures in Cambridge. In July 1946, his name appears for the first time in a partly coded remark in Wittgenstein’s manuscripts. The entry gives a touching impression of Wittgenstein’s emotional agitation at meeting Richards:

“I am terribly depressed. Quite unclear about my future. My love story with Richards has completely debilitated me. It has held me down, like madness almost, for the last 9 months. It is as if I have been running after a phenomenon with all my strength; sometimes with the hope of catching it, more often still in fear or despair. But I can’t reproach myself, i.e. I don’t blame myself. Was it good, was it bad? I don’t know. I can only say: it was my terrifying destiny.” (MS 130, p. 185, entry of 22.7.1946)

In the following weeks, the remarks about Ben Richards in Wittgenstein’s manuscripts pile up, all in the same tone of passionate love, but marked from the start by fears of loss. The fear that a relationship with a friend 35 years junior cannot last dominates him and weighs on him. He struggles to find a composed attitude towards the likely ending, which he expects at any time.

“May my heartache lead me to the right action. Can you imagine the following: that B. will grow completely out of love for you; namely, in the same way, that even as a young boy one no longer remembers what one felt as a small child and forgets all about the child’s affection, without sensing any disloyalty.” (MS 131, p. 26, coded entry of 12.8.1946)

At the end of September, beginning of October 1946, Wittgenstein spends two weeks with Ben Richards in Swansea. He feels that his inner equilibrium, as well as his capacity for philosophical work, is entirely dependent on his relationship with Ben Richards during this time.

“Everything comes from good luck! I couldn’t be writing like this now if I hadn’t spent the last two weeks with B. And I couldn’t have spent them like this if illness or some accident had intervened. – (!!!)” (MS 132, p. 147 coded entry of 8.10.1946).

“Can’t you be happy without his love? Must you sink into grief without this love? Can you not live without this support? For this is the question: can you not walk upright without leaning on this cane? Or can you not make up your mind to give it up? Or is it both? – You mustn’t always expect letters that don’t come! But how can I change it? It is not just love that draws me to this support, but that I cannot stand securely on my two feet alone.” (MS 133, pp. 42v, 43r, coded entry of 27.11.1946)

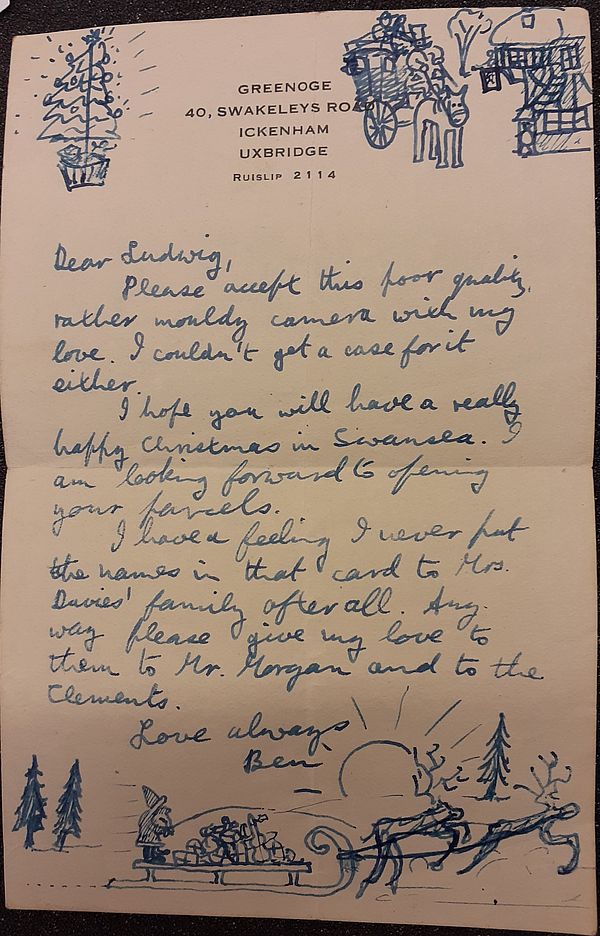

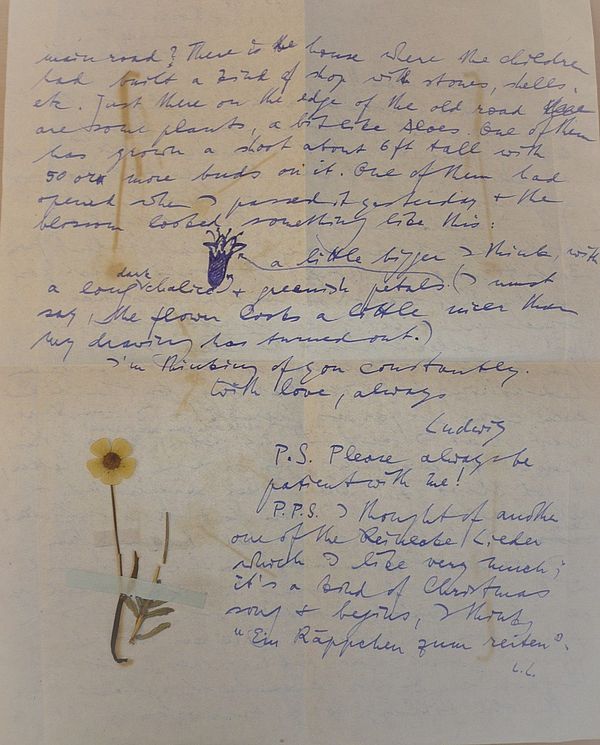

The correspondence in its entirety provides a detailed insight into the following years of this close bond. Wittgenstein repeats again and again that Richards has become for him the most important support and the only source of genuine joy in life. After each meeting with his friend, Wittgenstein thanks him effusively and emphasises how much he enjoyed their time together. He implores Richards to write regularly and complains bitterly about long breaks from writing, which always plunge him into depression. He expresses his feelings for Richards in almost word-for-word phrases such as “I think of you constantly with love” and “God bless you”. Wittgenstein encloses dried plants with many of his letters, and Richards also sends him these tokens of mutual affection.

Fig. 3: Letter from L. Wittgenstein to B. Richards dated 23.6.1948 with a dried plant.

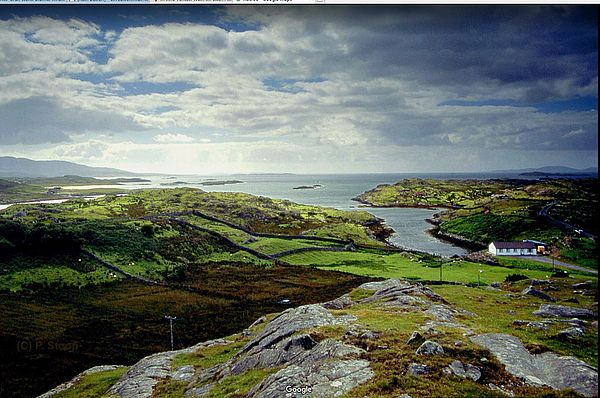

On weekends, Wittgenstein regularly visits Richards, who is completing his practical medical training at the Barts Hospital in London, or is visited by Richards in Cambridge. They spend holidays together in Cornwall and Swansea, Wittgenstein’s favourite holiday destination during this period. He takes a lively interest in Richard’s training as a doctor, tries to motivate him, and gives him support. After resigning his professorship in Cambridge at the end of 1947, Wittgenstein spends many months in Ireland, first in County Wicklow, later in Rosro, a remote place in Connemara on the Irish west coast. From his Irish solitude, he writes to his friend: “Your letters are food + drink for a whole week and that’s no exaggeration. … I have often been thinking that if it weren’t for you I couldn’t live here at all.” (Letter of 4 June 1948).

Fig. 4: The mouth of Killary Fjord near Rosro on the west coast of Ireland in Connemara, Wittgenstein’s place of residence in spring/summer 1948.

In the summer of 1949, Wittgenstein returned from an extended stay with his student Norman Malcolm in the USA, already severely marked by his ultimately fatal cancer disease. With Richards, who in the meantime had been able to complete his medical studies, he undertook a final trip to Norway in the autumn of 1950. Together they visit his house near Skjolden, which was built in 1914 and is situated in a lonely spot above Lake Eidsvatnet.

Fig. 5: View over Lake Eidsvatnet near Skjolden, Norway, Wittgenstein’s house on the far left.

At his death on 29 April 1951, Ben Richards was among the students and friends gathered at Wittgenstein’s deathbed. The relationship with Ben Richards had a significant impact, not only on Wittgenstein’s personal but also on the intellectual life of his last years. Remarks such as the following reflect Wittgenstein’s deep emotional relationship with Richards and show another side of Wittgenstein’s thinking that has hardly been noticed by those writing on his work until now.

“Love is the pearl of great value that one holds close to one’s heart, for which one does not want to exchange anything, which one values as the most precious thing one has. It shows you in any case – when you possess it – where the greatest value lies.” (MS 133, p. 8r ff., coded entry from 26 October 1946)

About the author: Dr. Alfred Schmidt is a scientific assistant to the Director-General of the Austrian National Library and Wittgenstein researcher.

________________________________________

Sources:

The entire Wittgenstein Nachlass is accessible online in the Bergen Nachlass Edition (BNE) published by the Wittgenstein Archive in Bergen on Wittgensteinsource.

(1) See the biography of the four Olivier sisters published in 2019 by Sarah Watling, entitled: Noble Savages: the Olivier sisters: four lives in seven fragments, ” Oxford University Press.

(2) Noel Olivier’s correspondence with Brooke was published in 1991 under the title: ” Song of love: the letters of Rupert Brooke and Noël Olivier (1909-1915), ” Pippa Harris (ed.), New York: Crown Publishing 1991.

Translation: Wittgenstein Initiative