WITTGENSTEIN AND VIENNA

by Ray Monk

"People nowadays think that scientists exist to instruct them, poets, musicians, etc. to give them pleasure. The idea that these have something to teach them - that does not occur to them." Ludwig Wittgenstein, Culture and Value

Though Wittgenstein is widely regarded as the greatest and most influential philosopher of the twentieth century, there is an aspect of his thinking that has been largely ignored by much of the work that has been written about him and inspired by him, even though he himself thought it centrally important to everything he did. That is his opposition to scientism, the view that all real knowledge is scientific knowledge, all real understanding scientific understanding.

In setting his face against this view, Wittgenstein drew on the art, poetry, literature, music and architecture that he loved best and which he regarded as the greatest flowering of European culture and one of the greatest expressions of human creativity. This was the culture he had grown to appreciate during his formative years in Vienna and much of it was itself Viennese. He loved, for example, the music of Brahms, who often came to the Wittgenstein family home, the Palais Wittgenstein, to play in its magnificent salon for the large family and their guests. Wittgenstein’s father, Karl, was a great patron of the arts, and two of Wittgenstein’s other favourite musicians, the violinist, Joseph Joachim and the composer, Josef Labor, were beneficiaries of Karl’s patronage. Karl also sponsored some of the great art of fin de siècle Vienna. He paid for the Secession Building and commissioned works from some of the Jugendstil painters who exhibited there, most notably Gustav Klimt’s splendid wedding portrait of Wittgenstein’s sister, Margarethe.

As for literature, Wittgenstein once said of the Viennese poet, Franz Grillparzer, ‘We do not know how beautiful he is’, and he loved, too, the work of other quintessentially Austrian writers, such as Ferdinand Raimund, Johann Nestroy and Nikolaus Lenau. Above all, among Viennese writers, Wittgenstein admired Karl Kraus, whose literary style and whose determination to strip away all artifice was a decisive influence on his way of thinking and writing. When, in the 1930s, Wittgenstein made a list of the people who had influenced him, the list included more Austrians than members of any other nationality. As well as Kraus, there were the philosopher and psychologist Otto Weininger, the architect Adolf Loos and the physicist Ludwig Boltzmann. Another towering figure of Viennese thought and culture, Sigmund Freud, is conspicuously absent from that list, but on more than one occasion Wittgenstein described himself as a ‘disciple of Freud’.

For over twenty years after his death, the importance of Vienna and Viennese culture in Wittgenstein’s life and his thinking were more or less ignored. Then, in 1973, Wittgenstein’s Vienna by Allan Janik and Stephen Toulmin was published and very quickly transformed the way Wittgenstein was read. Now, forty years after that, the Wittgenstein Initiative seeks to take the next step in reclaiming Wittgenstein for Vienna and Vienna for Wittgenstein. For what the city of Vienna is in a unique position to achieve is not only to show the world the importance of Wittgenstein’s Vienna, but also to demonstrate that Ludwig Wittgenstein was, in a very important sense, Vienna’s Wittgenstein.

By hosting events that help the people of Europe to rediscover the great art, poetry, literature, philosophy, and music of Vienna, we hope to keep alive the central Wittgensteinian insight that ‘poets, musicians etc’, as well as giving us pleasure, have something important to teach us, something that science cannot teach us. This will not only assign the city of Vienna its due importance in shaping the thought of Wittgenstein; it will also help all of us to assign to the arts their due importance in bringing us to a deeper understanding of our own humanity. In this way, Wittgenstein’s beloved home city can play an appropriately important role in helping us all to understand just why he is correctly regarded as the most important philosopher of the twentieth century.

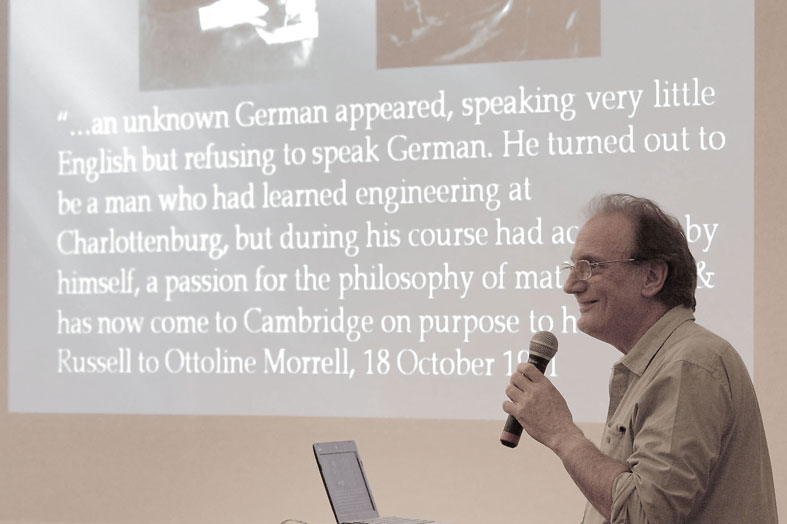

Prof. Ray Monk is a British philosopher and Professor of Philosophy at the University of Southampton, where he has taught since 1992. He won the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize and the 1991 Duff Cooper Prize for Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. Monk is also author of Bertrand Russell: The Spirit of Solitude & The Ghost of Madness. His interests lie in the philosophy of mathematics, the history of analytic philosophy, and philosophical aspects of biographical writing. His biography of Robert Oppenheimer was published in 2012.